Before the introduction of the national highway system in 1956, traveling the roads in the United States required passing through cities and communities to get to one’s destination. For various reasons, this could prove dangerous for out-of-towners who may wander into parts of town that the locals know well to avoid.

Such a prospect was especially true for negro motorists. During the era of Jim Crow, not only was traveling dangerous for negroes but their patronizing the wrong business had the added hazard of being potentially illegal under segregation.

In 1936, a black postal employee named Victor Green published a list of places in New York City that could be counted on as safe places for a black person to do business – whether it be getting gas, a hotel room or a drink and a sandwich.

The next year, he expanded the list to include other cities as well. As demand grew, so did the publication and it eventually included information for all the states in the union. Before ceasing its publication in 1964, it was the most popular resource for traveling black tourists in the US.

The creation of the interstates in 1956 and the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 made the book obsolete, but copies live on to commemorate this interesting, if dark reminder, of a chapter in American history when a free man was only as free as the liberality of the city he was in.

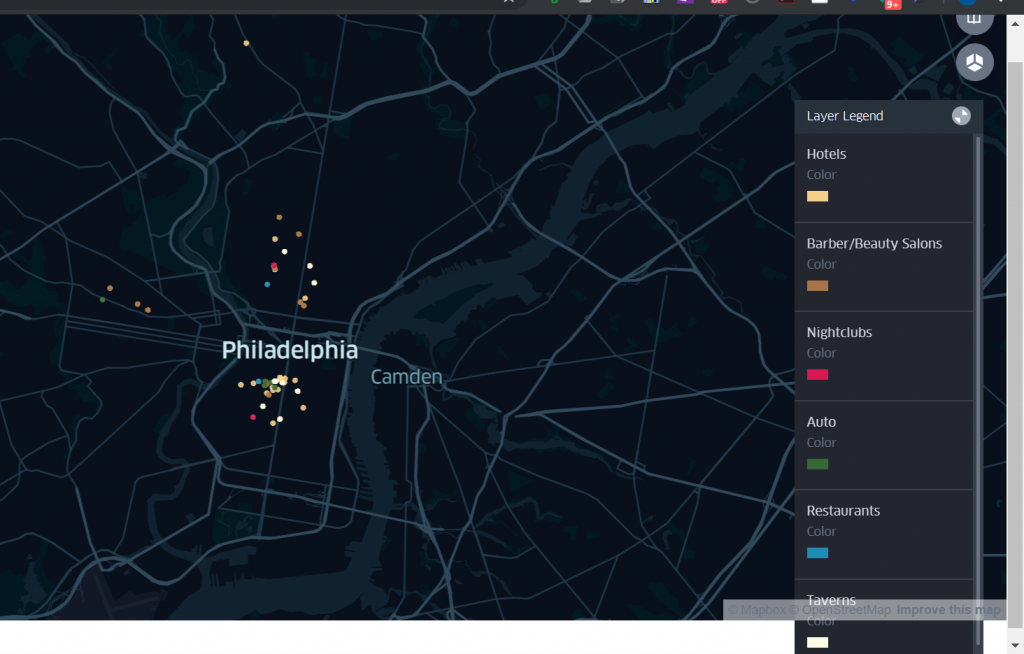

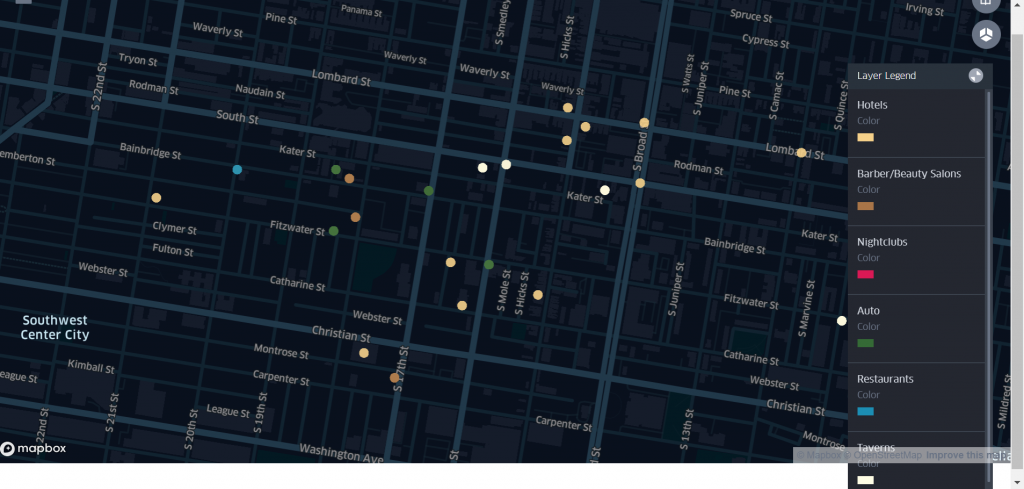

Using a copy of “The Negro Motorist Green Book” from 1940, I cataloged the entries for Philadelphia at the time. The list includes five garages, fifteen barbershops and beauty salons, eighteen hotels, two nightclubs, two restaurants and nine taverns for a total of fifty-one total businesses listed. Twenty-nine of these are located in South-Central Philadelphia

As you can see, some substantial clustering occurs.

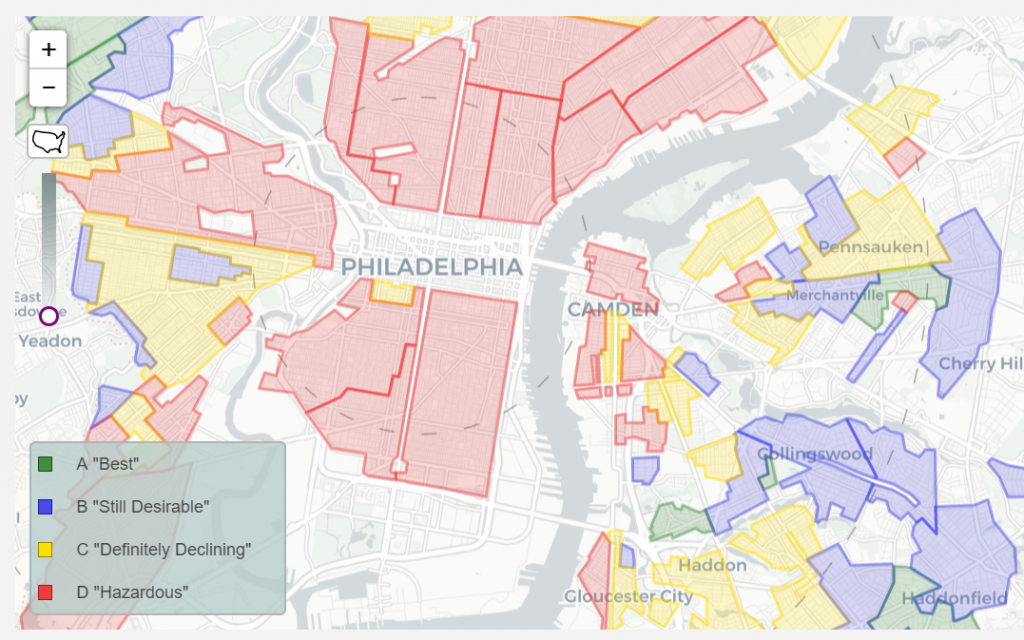

In the first 100 days of the Roosevelt Administration, legislation was passed as a part of the New Deal to help restructure the housing lending market. This included what is referred to as “redlining”. Cities were carved up with lines demarcating desirable and undesirable locales. Those falling within so-called “redlines” were properties not eligible for mortgage loans as they represented “dangerous” parts of the city.

The following is a copy of the redlined districts in Philadelphia in 1940. Compare the redlined map below of the same area represented above:

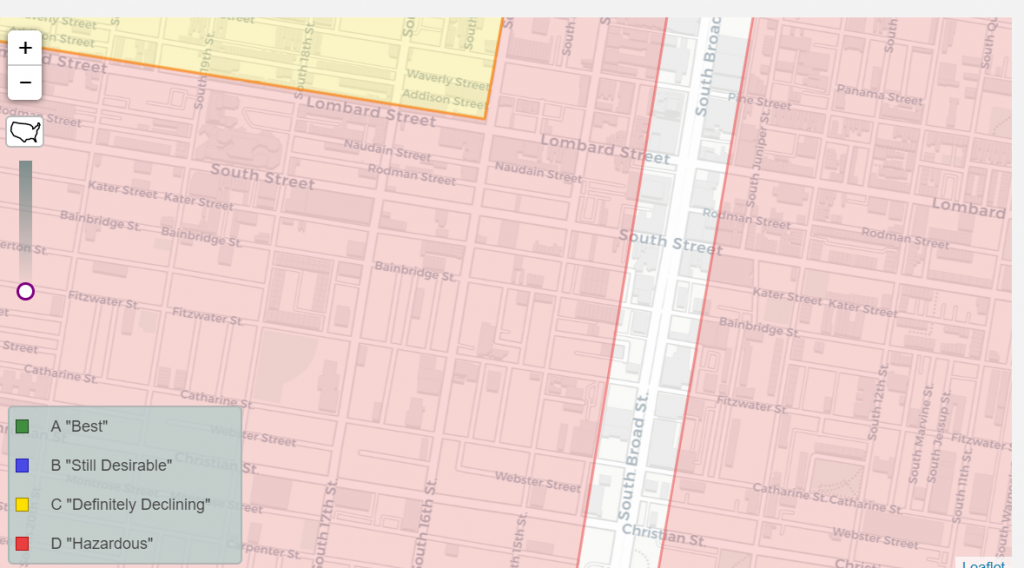

Below is a closer view – one can orient themselves by finding the intersection of S. Broad and Lombard Sts.

As we can see, all these properties fall within an undesirable, if not “Hazardous” area of town. As such, mortgages would not be granted for people applying to purchase properties in those areas. That means that only those with the ability to pay cash for these buildings would own them.

Thus begins the systemic economic crippling of the black person in the city. Rich, white property owners held the deeds to their homes and charged whatever rent they wanted. This perpetuated the poverty of the lower class blacks and while their civil rights were guaranteed in 1964, the economic mobility required to capitalize on those rights was and is still lacking.

References, Resources and Picture Credits:

BlackPast – THE NEGRO MOTORIST GREEN BOOK. May 15, 2019. Accessed July 16, 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/negro-motorist-green-book-1936-1964/.

Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al., “Mapping Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, accessed July 16, 2019, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=12/39.9634/-75.1710&opacity=0&city=philadelphia-pa&text=bibliographhttps://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=12/39.9634/-75.1710&opacity=0&city=philadelphia-pa

“The Negro Motorist Green-Book: 1940.” NYPL Digital Collections. 2019. Accessed July 17, 2019. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/dc858e50-83d3-0132-2266-58d385a7b928.Tunnell, Harry. “The Negro Motorist Green Book (1936-1964).”